Stanley and Livingstone were arguably the best-loved vaudeville act in the history of Victorian London, in addition to being disguised space aliens sent to colonize earth....wait, bear with me for a minute. Okay, someone hacked this Wikipedia page. Please ignore the previous sentence.

Stanley and Livingstone were intrepid travelers who did, in fact help to colonize

part of the earth: the part called Africa. Both men impacted the course of African history in ways good and bad (mostly bad, if you were an African).

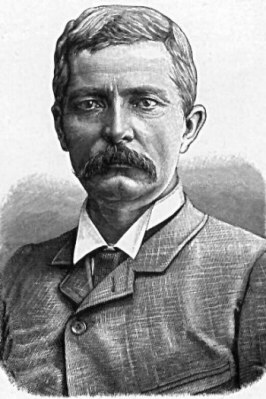

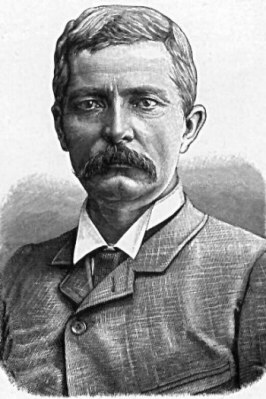

David Livingstone

David Livingstone (1813-1873) was a famous, indeed almost mythical, British national hero. His roles as Christian missionary, geographic explorer, and anti-slave trade abolitionist granted him great fame in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. He is well-known today for "discovering"

Victoria Falls and being the subject of one of the most famous phrases in Western culture. He tried to find the source of the Nile River, but didn't.

Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904) lived one hell of a life. A journalist and explorer, he was born in

Wales, but moved at a young age to America. He reluctantly served in the American Civil War, eventually having the distinction of deserting both the Confederate and Union forces. After that nifty trick, he became a journalist. In 1869, while a correspondent for the

New York Herald, Stanley was recruited to mount an expedition into Africa to find Livingstone, who had not been heard from for six years. And find him he did.

Stanley's 700 mile, eight month expedition into present-day Tanzania, including around 200 porters, culminated on November 10, 1871 near Lake Tanganyika. Upon finally coming face-to-face with his quarry, Stanley uttered one of the most famous greetings in history: "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?"

Or maybe he didn't. Let's just say he might have. Livingstone's account doesn't mention what would seem to be a singular way of addressing someone you've just met. And Stanley himself tore out the pages of his diary that recount

the meeting. At any rate, it made for great reading in the papers. Stanley's books, including

How I Found Livingstone and

Through the Dark Continent, made him a renowned and successful explorer, and financed his other trips to Africa.

Livingstone stayed in Africa after his famous meet-and-greet with Stanley. Eventually he got sick and died of malaria and internal bleeding. He had spent so much time in Africa that his six children grew up fatherless, and his wife also died of malaria trying to journey to Africa to meet him. Livingstone's heart was buried under a tree, and his body was taken to England by his two loyal servants,

Chuma and Susi.

Stanley tinkered around in Africa for awhile, eventually signing on to help King Leopold II of Belguim to claim lands and introduce "civilization" and Christianity to the Congo. We will read much more about that in

King Leopold's Ghost, so suffice to say that Stanley spent a lot of time in his twilight years defending himself against charges that his expeditions in Africa were needlessly cruel and brutal, plagued by savage beatings and exploitation. Predictably, he was also knighted.

Here's a link to a video made by a bunch of twerps for a class project:

Dr. Livingstone's African Journey.